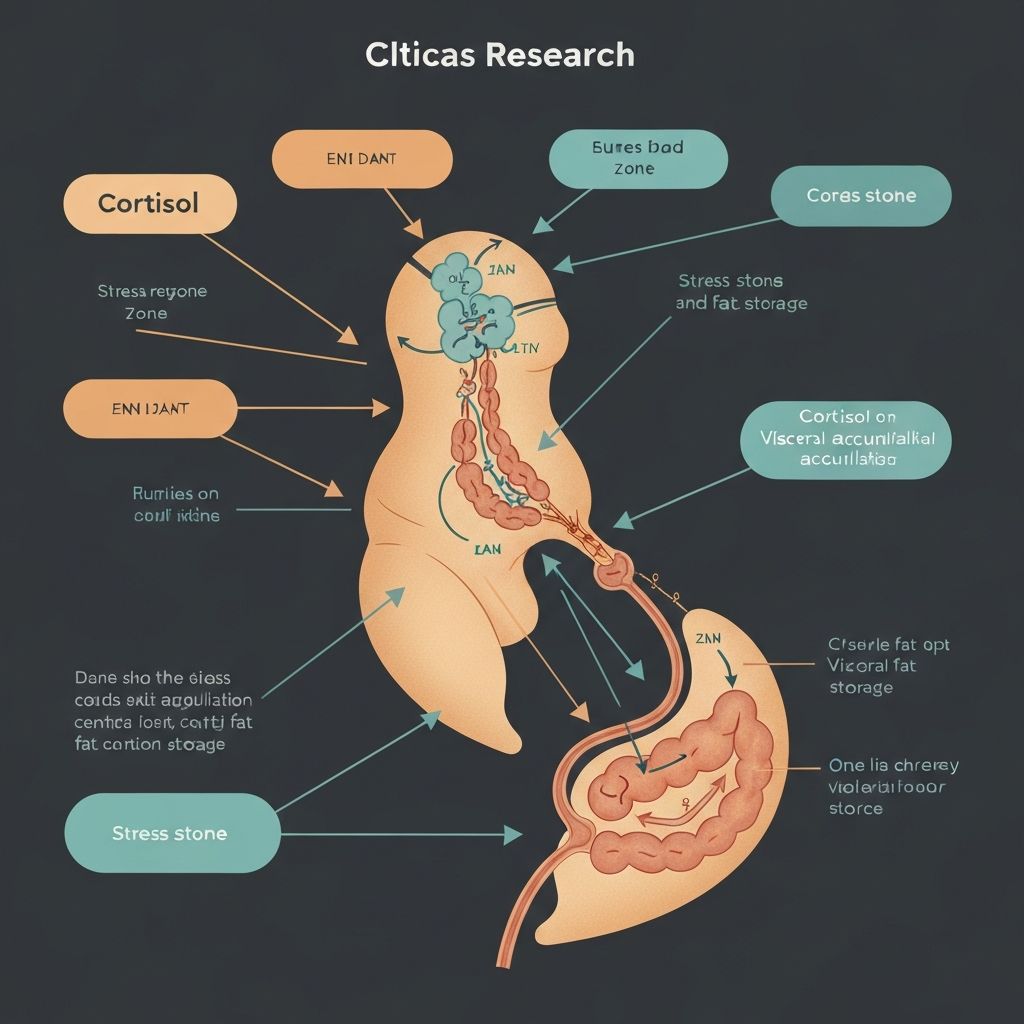

Cortisol's Role in Preferential Central Fat Storage

Exploring stress hormone effects on abdominal adiposity and glucocorticoid influence on fat distribution patterns.

The HPA Axis and Glucocorticoid Production

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents the body's primary stress response system. In response to perceived or actual physiological stressors, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then signals the adrenal cortex to produce and release cortisol, the primary human glucocorticoid hormone.

Under normal conditions, cortisol demonstrates a characteristic diurnal rhythm, with peak concentrations in early morning hours and nadir values during late evening and sleep. This pattern reflects circadian regulation and supports physiological functions including glucose mobilization, immune regulation, and metabolic adjustment across waking and sleeping periods.

Chronic Stress and Dysregulated Cortisol

Prolonged psychosocial stress, occupational demands, sleep disruption, or chronic inflammatory conditions can produce sustained HPA axis activation and elevated cortisol concentrations. Unlike the adaptive acute stress response, chronic elevation of cortisol represents pathological dysregulation with multiple metabolic consequences.

Chronically elevated cortisol concentrations demonstrate associations with increased abdominal adiposity and visceral fat accumulation in both clinical observations and research cohorts. Interestingly, this relationship is not simply dose-dependent; dysregulated diurnal cortisol patterns (for example, failure to demonstrate adequate morning elevation or evening decline) associate more strongly with central adiposity than absolute cortisol concentrations alone.

Mechanistic Effects on Adipocyte Biology

Glucocorticoid receptor expression varies substantially across adipose tissue depots, with visceral adipose tissue containing higher densities of glucocorticoid receptors compared to subcutaneous reserves. This receptor distribution helps explain preferential visceral fat expansion under elevated cortisol.

Cortisol influences adipocyte differentiation by enhancing the expression of key transcription factors involved in fat cell development. It promotes the conversion of preadipocytes (immature precursor cells) into mature, lipid-storing adipocytes. This effect is particularly pronounced in visceral compartments due to differential receptor expression.

Lipogenic Gene Expression

Cortisol enhances the expression of lipogenic enzymes—proteins that synthesize and store fat—particularly in visceral depots. Key enzymes affected include:

- Acetyl-CoA carboxylase - catalyzes the first committed step in fatty acid synthesis

- Fatty acid synthase - synthesizes long-chain fatty acids for storage

- Lipoprotein lipase - hydrolyzes circulating triglycerides for uptake into adipose tissue

- Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase - facilitates triglyceride synthesis

Enhanced expression of these enzymes promotes net fat accumulation in visceral compartments. Simultaneously, cortisol suppresses the expression of hormone-sensitive lipase and other enzymes involved in fat mobilization, creating a storage-favoring metabolic state.

Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Resistance

Elevated cortisol impairs glucose metabolism and promotes insulin resistance through several mechanisms. Cortisol antagonizes insulin signaling, suppresses glucose uptake in muscle tissue, and enhances hepatic glucose output (gluconeogenesis). These effects elevate fasting glucose and hyperinsulinaemia.

As discussed in detail in our insulin-focused article, hyperinsulinaemia itself promotes preferential central fat storage. Thus, cortisol-induced insulin resistance creates a secondary mechanism driving abdominal adiposity independent of its direct adipocyte effects.

Substrate Partitioning and Energy Storage

Cortisol influences whole-body substrate utilization patterns, promoting preferential storage of dietary macronutrients as fat rather than utilization for energy production. It inhibits protein synthesis and promotes protein catabolism (muscle breakdown), while simultaneously promoting lipid storage. This metabolic milieu favors net fat accumulation, particularly in visceral compartments.

Free Fatty Acid Mobilization and Portal Delivery

Chronic elevated cortisol increases circulating free fatty acid concentrations by promoting lipolysis (fat breakdown) in subcutaneous adipose tissue. These elevated free fatty acids are delivered to the liver via the portal circulation, promoting hepatic lipid accumulation and triglyceride synthesis. The combination of cortisol-promoted visceral fat accumulation and increased portal free fatty acid delivery creates particularly unfavorable hepatic metabolic circumstances.

Research Observations in Stress Populations

Occupational cohort studies of high-stress professions (medical residents, military personnel, high-pressure corporate roles) document associations between stress measures and central adiposity. Population studies similarly show that self-reported chronic stress and measured cortisol dysregulation associate with increased waist circumference and visceral adiposity.

It is important to note that these observations demonstrate associations but do not establish simple causation. Stress and cortisol dysregulation interact with numerous other factors including sleep disruption, altered eating patterns, and reduced physical activity—all of which themselves promote central adiposity.

Circadian Disruption and Central Adiposity

Modern lifestyles frequently disrupt the normal circadian regulation of the HPA axis. Shift work, irregular schedules, chronic sleep deprivation, and evening light exposure all impair normal cortisol rhythm patterns. These circadian disruptions associate with central adiposity accumulation independent of total stress burden.

Recovery of normal sleep-wake cycles and circadian alignment has been shown in intervention studies to improve cortisol rhythm patterns and associate with favorable changes in abdominal adiposity measures in some populations.

Educational Note

This article describes physiological mechanisms linking cortisol and stress hormones to abdominal fat accumulation. Individual stress responses and cortisol regulation vary substantially based on genetics, personality factors, social support, and prior experiences. This information is educational only and does not constitute medical or stress management guidance.